“I‘m asking for more commitment in support of the military-industrial complex, in order to obtain additional funds for new armed systems and enforcement the of the European defence with the constitution of new military divisions coordinated with NATO‘s intervention force.”

Minniti in 2006

The 12th of April 2017 the Italian government approved two decrees regarding immigration and security. The laws are signed by the new ministry of the Interior, Domenico (alias Marco) Minniti. Behind them, there is the embitterment of measures driven by the logic that persist in treating migration’s phenomena with police and military instruments of governance and contention; the same logic that persecutes organisations of mutual aid and opposition movements in a warlike manner. The renewed pervasion of intervention of a boosted public force is justified in the name of a securitarianism alarm. The institutions proclaim themselves as interpreters of a “widespread perception of insecurity”.

The profile of the neo-ministry leaves no doubts about the interests linked to his mandate. The curriculum vitae of the “sub-secretary of defence for cooperation with UE, NATO and US and arm industry promotion” during the Amato‘s government (2000 – 2001), has recently been reconstructed.1 It would be enough here to recall that he is also the founder of the agency ICSA (Intelligence Culture and Strategic Analysis) together with the ex-president Cossiga (the repression‘s strategy of which are sorely well known2). A centre of study in matters of intelligence and military defence, this political foundation “boasts” to have as members of its board a high officer of NATO, commandants of specials forces, and permanent members of OSCE. This organisation works in collaboration not only with secret services, but also with the Italian industrial confederation and receives business oriented funding from the private industrial sector.3

Illegalisation and detention

It has recently been shown (by the Antigone association) that the measures of the decree on the matter of immigration will aliment the mechanism of production of illegal individuals.4

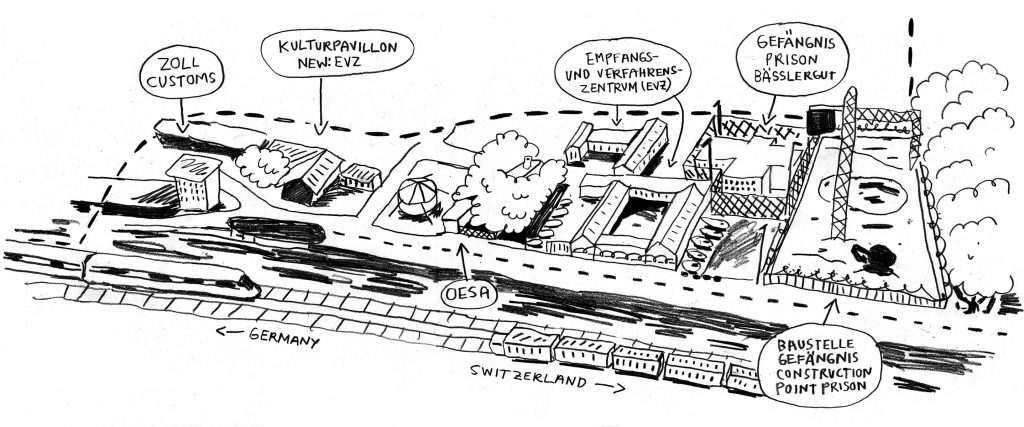

With the reinforcements of the French, Austrian and Swiss borders, the electronic taking of fingerprints (perpetuated with the use of force and without legal basis by the hotspots structures) prevent migrants from seeking asylum in other states, landing in a trap situation inside Italian territory.

Among the measures of the decree, there is the abolition of the appeal proceedings in the asylum request procedure. Furthermore, there is no obligation on the part of the judge to listen to the asylum seeker. In short, the refusal of the request by the “territorial commissions” arrives without the right to be heard and is not contestable if not in third degree.5 The government codifies by facts the existence of a juridical system with two different parameters: A distinct juridical apparatus for foreigners that dismiss the guarantees.

The decree reintroduces and potentates the disastrous coercive answer that caused the installations of dis-human structures like the C.I.E. (Centers of Identification and Expulsion). The law establishes new detention institutions (called Centers of Permanence for Repatriation), it increases their numbers and enlarges the typology of forced detentions. The time limits for the permanence are also prolonged.

“The very concrete risk is that it will increase, in dimensions and impact, a specific detention circuit for foreigners that would be deprived of even the minimum of guarantees of the penal sector.”6

The measures of the decree go hand in hand with the police agreements made between the Italian government and some military troops of the Libyan Coast Guard, with Tunisia, and Niger. The agreement with Libyan authorities – the contents of which have come partially to light last February – has as its objective the patrolling of the coasts, the financing of Libyan detention structures and the military support in the closure of the southern border that separates Libya from Nigeria. In synergy with the EU and the Frontex agency, the Italian government trains military units, supplies patrol boats and will provide radar monitoring structures.7

The text of the law also mentions that the allocation of funds aiming to send troops in protection of Italy’s commercial interests in Africa.8

The critiques raised against the immigration decree have denounced its propagandistic character; its purpose to pry the “monopoly of the narrative of the immigrant danger” out of the hands of political forces on the right, in order to cynically ensure the calculated electoral pay-off.

Juridical associations exposed the inadmissibility of the emergency legislation in those matters, they point the finger to the violation of the European Convention on Human Rights and the unconstitutionality of the laws.

But on a basic level, much more is at stake: a common design is traced between the two decrees, at the heart of which there is a precise idea of social order. This normativity, strongly exclusionary, is structured in synergy with the interests of military and commercials holdings. It takes shape through a vertical management of social conflictuality and it relies on techniques of disciplinarian and capillary control of mobility.

The targets of the punitive-administrative measures are individuals or categories that are considered politically undesirable; marginalised by the economic crisis or suspects for the economical-productive apparatus as not- extractable forces.

Militarisation and mobility control

The decree in regard to security denies resources to the local administrations, preventing them from implementing social policies in support of the living conditions of the less well-off, instead, it authorises mayors and prefects to persecute the poor segments of the population with police and administrative actions.

It is illustrative, in this sense, that one entire article is about the promotion of the exacerbation of repressive police action against the “arbitrary” occupations of buildings and the legitimisation of the increment of the use of force during the evictions.

Those measures affect the subjects fighting for the right to housing and put them in even greater danger. Subjects to whom the residency (status that ensures civil rights like the access to public health) have already been deprived by previous legislation which prevents those who occupied a place from attaining residency and asking for running water and electricity. The same measures apply to the non-residential occupations, preparing the legal ground for the embitterment of the use of force in situations of organised political dissent and in the persecution of solidarity and mutual aid associations.

The legislation about the “decorum”, contained in the security decree aggravates the punishments for “whoever engages in conduct that prevents the access and the fruition of rail and public transport infrastructures (stationary and mobile) and their appliances, in violation of no-stopping zones”.

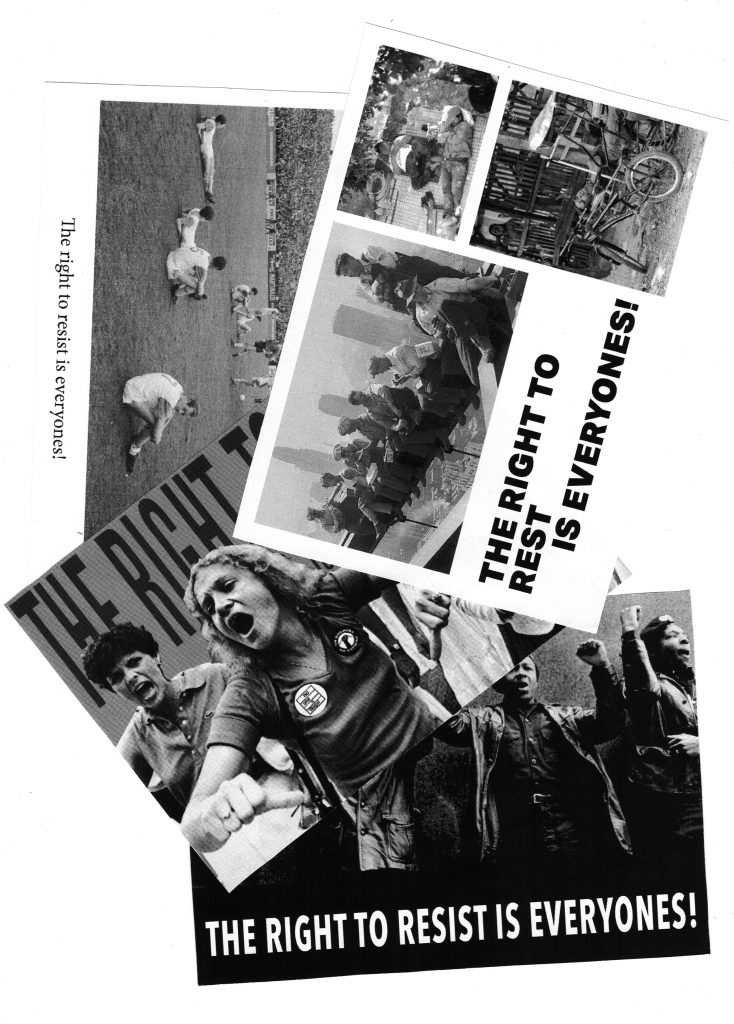

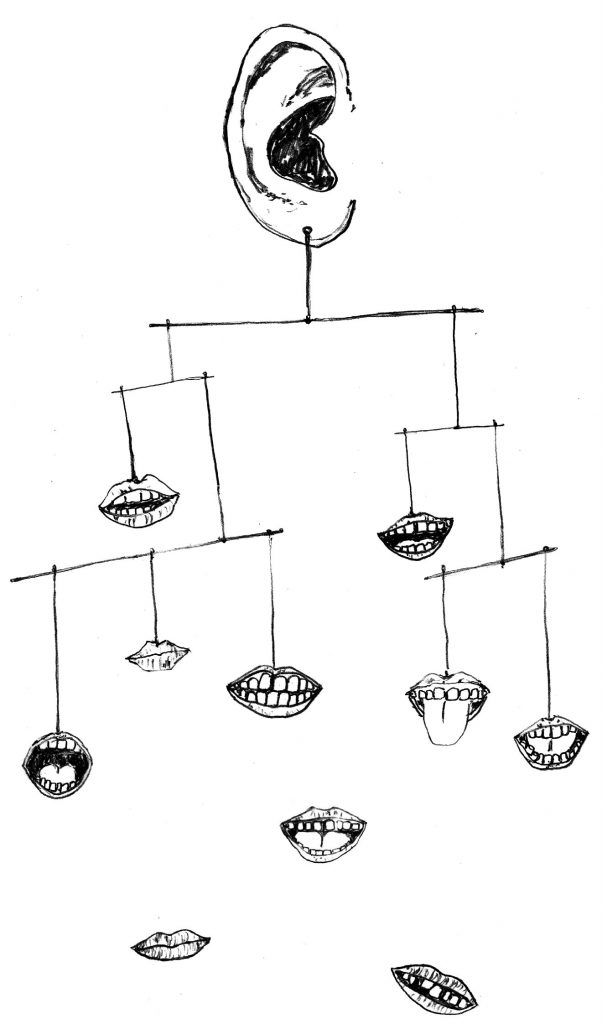

It is not hard to understand how any kind of collective demonstration could easily fit within this label. Besides the evident objective of the legitimisation of the use of force as an instrument of contention of political struggles (through the criminalisation of pickets, demonstrations, strikes and every temporary blockage of the flow of production), the mention of “internal areas” of rail stations and other public places likely to provide shelter leads to a further, bitter, reflection: even resting or making a stop can be used in different way by the securitarianism policy.9

If the state is dealing with a docile residential citizenship to reassure, sleep became the good to protect, the pretext for a widespread surveillance of the quarters10; but if it deals with who is leaving with great difficulty, who found himself marginalised, then his rest can be constantly opposed and authoritatively denied.

In the era of “integrated security”, the relief from fatigue is a good in which governance invests, that can be allowed in differentiated ways and became a right for the few. No-stopping zones, orders to leave, red zones and other sanctions are put at the discretion of police forces and local administrations. In this way, those who are subject to those measures are deprived of the guarantees of the penal sector. Those orders have a strategic character.

“The battle for decorum has to be read in strict connection with others political conflicts in which the implementation of administrative instruments is common. Oral advises or expulsion orders delivered in val Susa and in other cities with active social movements are illustrative. Besides the gap between declared aims and effective objectives, they also show the improper use of those measures.”11

The interdiction of the territories “of interest” has important precedents in the governmental measures aiming to hit oppositions movements as the No TAV fights in val Susa or the movement against the construction of the TAP (Trans Adriatic Pipeline) in Salento. In 2012, Berlusconi‘s government labelled the territories of the TAV as “areas of strategic national interest, in which access is denied in the military interest of the state”. With Renzi‘s governmental measure of 2015, the prohibition was also applied to the zones of construction of the TAP, as territory “characterised by nation priority and strategic interest”.

The synchronicity of administrative measures and territorial militarisation against a population treated as “internal enemy” is not entirely new. Those mechanics are activated in favour of multinational consortium and industries and follow a purely police logic that establishes “a singular hierarchy of importance between the safety of things and the safety of people”.12

The effects of this management of order and decorum didn’t wait long to show up. Some administrations even acted pro-actively, as in Bari where the communal administration tried to crackdown on activists and collectives before the G7 finance summit. In Bologna, the G7 on Environment has been preceded by the delivering of expulsion orders. In May 2017, under the order of the prefecture, the police (with helicopters and mounted troops) blocked the exits of Milan‘s train station and executed searches of people and controls on all the subjects of non-Caucasian racial groups. During the same month, in Rome, Niam Maguette lost his life in the attempt to escape from a police raid. His crime? He was a street vendor.