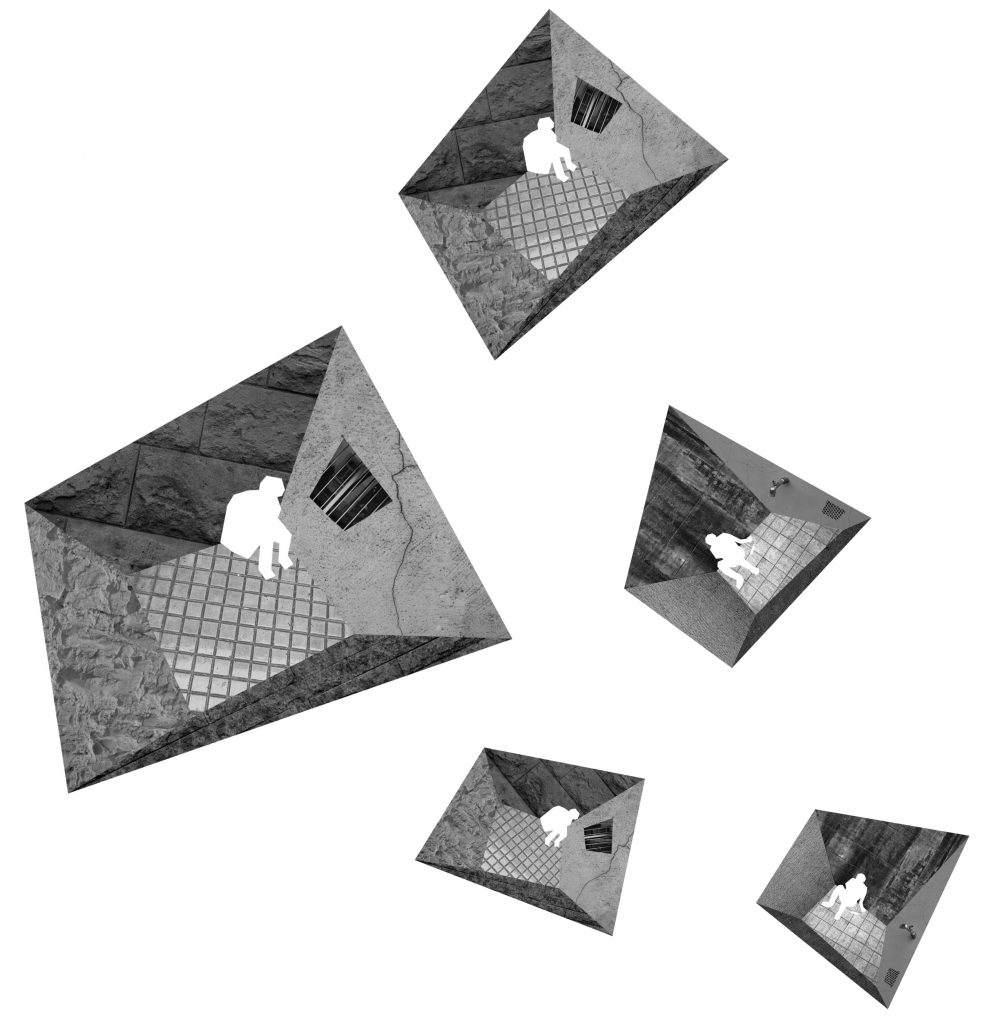

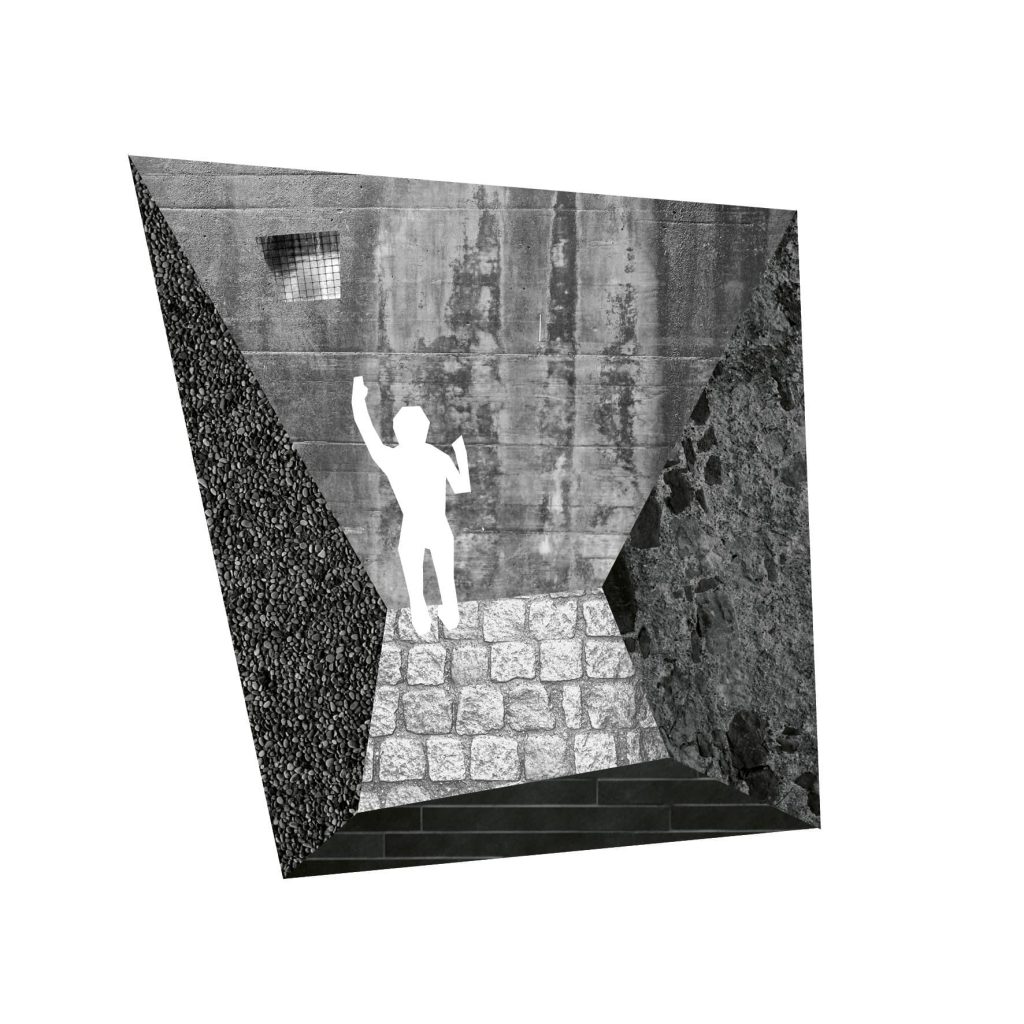

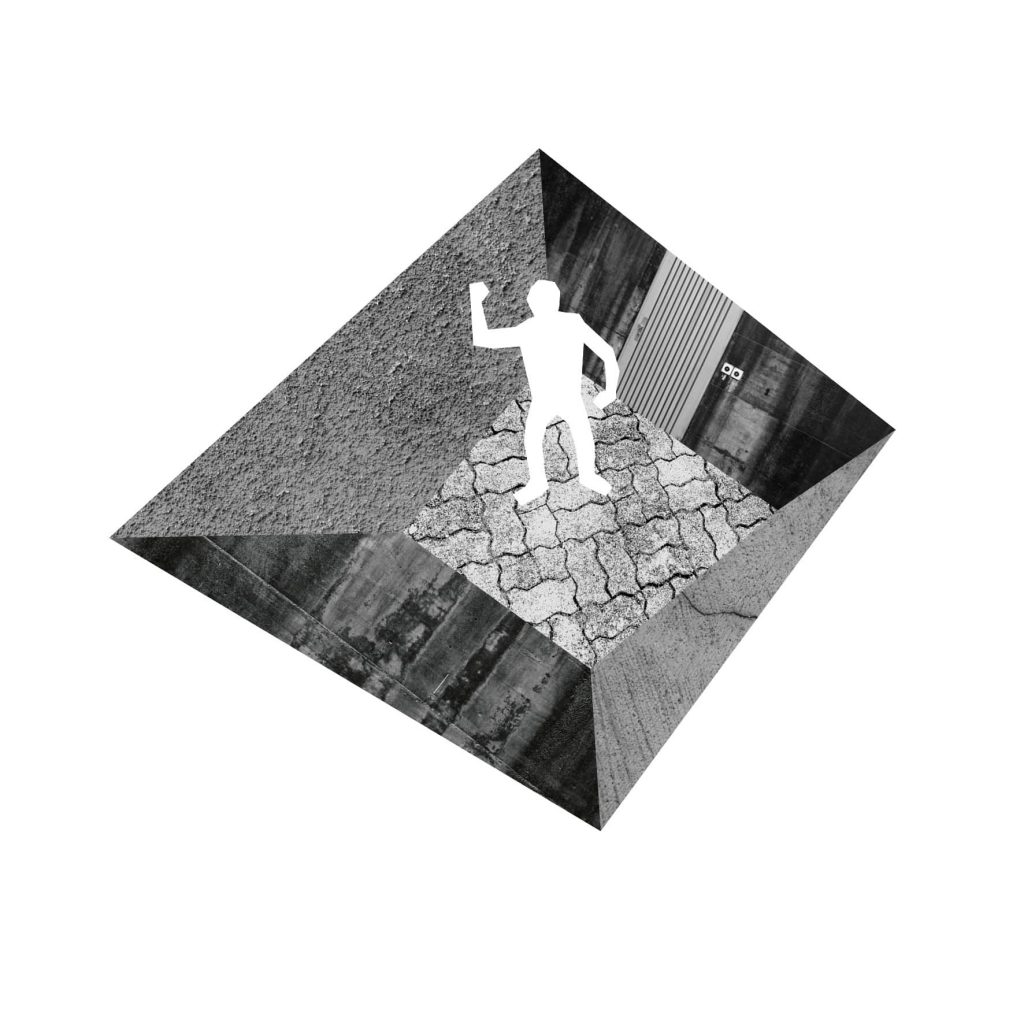

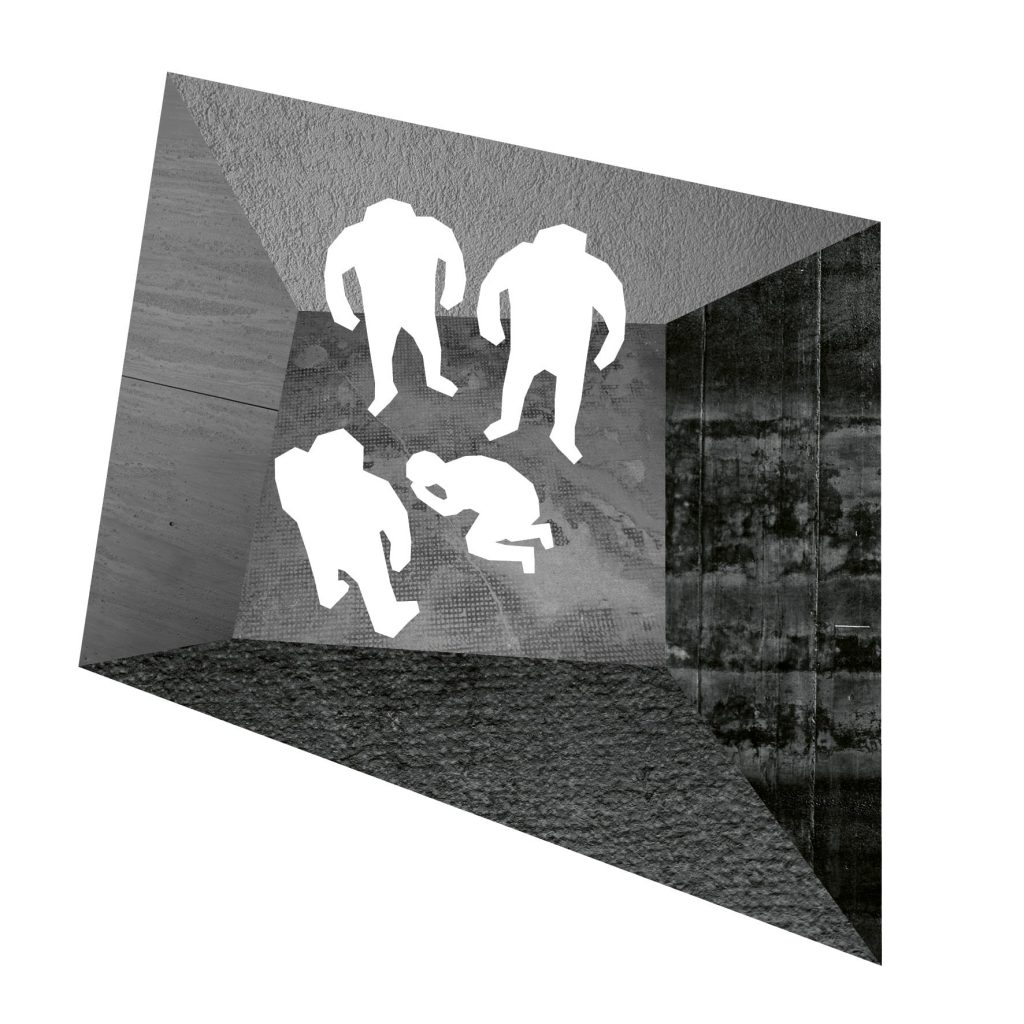

The photographs were taken during an official guided tour within the prison Bässlergut. Glances at the reception cell, the production room, the yard, the courtroom, the isolation cell, and the prison’s own kiosk. Then, we are back at the big steel gate separating the two worlds from each other. We were not allowed to take pictures of prisoners or personnel. What remains are empty rooms and the traces of human beings imprisoned.

Shaking the structures of relationships

The following sections list some resistant actions and forms of protest. The selection is neither comprehensive nor representative. It is a work in progress, looking for what is there to get inspired from and find more clarity for yourself. Whom should be reached and what is to be achieved? What is the potential and consequences of these different actions? In the framework of one‘s own ideology and the resources available, what would be possible? How does the action change in other context? Finally, this should encourage people to recognize themselves as part of a world in which not everyone thinks and acts the same way – and where many have the courage to put something against regimes and existing orders in the world.

The examples do not directly concern the migration regime, but still resist the structures of our society that make such a regime possible. For the sake of diversity, I rated the examples differently and enlisted various motivated actions, people with various scopes, means and goals.

http://www.ainfos.ca/04/aug/ainfos00112.html

https://www.metronaut.de/2012/05/medienhacking-im-wandel-kommunikationsguerilla-politischer-aktivismus/, http://kguerilla.org/de/afrika

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/05/19/nyregion/as-art-tania-bruguera-lives-like-a-poor-immigrant.html?pagewanted=all&_r=1&

http://www.linkfang.de/wiki/Roter-Punkt-Aktion

http://www.taz.de/!1167421/

https://spacehijackers.org/

For example an online test: https://spacehijackers.org/amIananarchist/index.html

http://theinfluencers.org/en/biotic-baking-brigade

https://www.vice.com/de/article/znk3vw/die-neuen-mauertoten-europas-772

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GIVvBF_7JDo

From the anthology Cultural Activism – edited by Begüm Özden Fırat and Aylin Kuryel

https://www.nadir.org/nadir/initiativ/agp/free/tute/

https://www.azzellini.net/zapatisten/die-tute-bianche-weisse-overalls

https://medium.com/@AreYouSyrious/ays-daily-digest-05-01-2018-the-trickle-down-effect-d957f1623b03

https://indymedia.org/de/2006/03/835732.shtml

-Other books about creative interventions:

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/755962.The_Interventionists

-Manual of the guerrilla communication , which describes and discusses different forms of it:

http://kommunikationsguerilla.twoday.net/topics/a.f.r.i.k.a.-texte/

-The Situationists and Dadaists, who unfortunately did not make it to the list anymore:

http://library.nothingness.org/articles/SI/en/

-Anarchist cooking books:

https://de.scribd.com/doc/11251441/The-Anarchist-Cookbook-by-William-Powell-1971

http://bnrg.cs.berkeley.edu/~randy/Courses/CS39K.S13/anarchistcookbook2000.pdf

https://crimethinc.com/books/recipes-for-disaster

-A podcast about the International Hedonist:

https://cre.fm/cre185-hedonistische-internationale

-Explanation and discussion about further direct actions :

Direct action by David Graeber

During the preparation of the list, the author has considered that it is good to have an awareness of what people want – to provoke – to point out – to express emotions – to organize and to form bonds – to deconstruct relationships – to look for alternatives – to live utopically – to get media attention on a topic – just turn to a topic and do something with it – show solidarity – spark a debate – pursue a concrete goal – to create parallel organizations and alternative ways in the existing system – the living conditions in the given structures / Improve situations. Furthermore, the difficulty of agreement of purpose and action, the injustice in the different scope of action, the conflict between intention and result, the relationship and the perception in the use of different means in given contexts, the instrumentalization of the situation against the people resisting – or whether it sabotages the real goal or the ideology – and why. She hopes that readers will be inspired by the examples that suit their own actions or – even better – by what is only half pleasing and think about how should it be changed in order to make sense for them.

Police-officer or pigs? on the use of language in FIASKO

The following article describes a discussion about termonaligy in german. The FIASKO would like to point out that the points being made (1-8) are not tied to any languae specifically.

As usual, following the launch of the last issue of FIASKO, an open discussion event was held, intenting to be a platform for evaluation and suggestions for the magazin. One subject that was discussed and criticized on that event was the use of language in FIASKO. Terms like „Bullen“ (meaning=the police, comparative in english to „the cops“) and „Knast“ (meaning=prison, comparative in english to „can“, „jug“) would be chilling and put some of the readers off. These readers might label the magazin as „far left“. This might diminish the range of the magazin, because some people would not feel addressed and might slip into a defensive attitude twards FIASKO.

This magazin defines itself as a critial intervention against migration-regimes and with that, an overall criticism of our society follows. One could say, this is „far left“. Some questions come up: Who‘s afraid of this position? And why? What does it mean to us that some people take FIASKO that way? Who do we want to reach? And by what means? How can we make content and points of view clear and at the same time mediate them in a way that readers are open to them altough some topics and formulations are uncommon or new to them? With the following points we would like to address the criticism of the use of language and share some thoughts on this point at issue:

1. The (German) language is an expression of the patriarchal system, that we live in today. So to speak it would be desirable that with new conceptions there is room for new terms, words and even sentence structure. If so it is possible to give rise to new thinking structures.

2. We see a connection between the use of language and critique of society. For example the gender star (*) used in german or the use of the term „geflüchtete Person“ instead of the patronising term „Flüchtling“. We welcome a courageous handling of language and terminology.

3. Consistancy plays an important role. If someone stumbles accross a word that provokes her/him, this can lead to lack of comprehension and dissociation. At the same time this will perhaps spark a fundamental content-related discussion.

4. One can argue over terminology and the use of language. In this example in perticular we belive that using terms like „Gefängnis“ instead of „Knast („prison“ – „can“) and „Polizist*innen“ instead of „Bullen“ (Policeman/Policewoman – „Cop“) can be downplaying in certain context. The language loses it’s clarity. At the same time one can criticise that these terms that are more conventional do not promote new images, do not encourage a new way of thinking and can not be used in a unexpected way. So to speak they remain in a certain slang.

5. The FIASKO-Kollektiv does not have a homogeneous language (with a few exceptions, see pont 8).It is important to us, that every author can decide individually which terminology they want to use. There are no set rules for the use of languguage, as you can see in this issue as well.

6. Having said that we want to make clear that we do not have an unambiguous position for such Terms, it wouldn’t be fitting to us. More important is that a concious, reflected and emancipatory use of language is applyed that fits the text that the author wrote.

7. To a concious handling of languague follows critical self-reflection. What happens when a term turns mainstream? Did the desired change happen or did the emancipatory character lose its meaning? Has the term become an empty words in meaningless phrase? Has the term become discriminating and excluding? etc.

8. Nervertheless, some limitations are important to us. In FIAKSO all texts (in german) should have gender stars. In this way people that do not, can not or don’t want to define themselfs as neither man or woman can be taken into account. Futhermore sexist, patriarchal, antsemetic, or discriminating use of language is gernerally unwanted.

…the next discussion-evening will follow and more texts aswell. Besides all that talking we should not forget to act, yalla!

Migration Management and the IOM

I was once asked the question why my criticism of the migration regime is limited to nation states, borders, capitalism, hegemony etc. After all, the “International Organization for Migration” (IOM) is a truly nasty organization that deserves to be the target of resistance as much as the other entities. Obviously there have been, and still are, many people who have grappled with the IOM, collecting information and data and criticizing it. But I felt called out and wanted to research the IOM as another agent who influences how migration policy is being made by states.

I see the racial profiling of people with dark skin by the police as a systematic practice, not because I think all police are Nazis, even though many can be found amongst their ranks, but because of the frequency and the obvious motive to make these peoples’ lives in Switzerland hell. This systematicity gained further significance for me when I read that this practice is part of a concept that has gained in popularity in the last 20 years. This concept is called “migration management” and is now the consensus amongst liberal states of how to deal with migration. The IOM plays an important role in the propagation and realization of the concept which they call a “global strategy”. This article is an attempt for readers to familiarize themselves with the IOM’s concept and to share certain thoughts about it.

Migration Management

“Migrations Management” was developed by the IOM to radically modernize the measure of control over the movement of persons a state can have. They do that by seeking to implement a universal administration in the various countries and the different forms of migration. These forms are divided into three categories (legal, illegal, and forced migration), despite the many personal reasons for leaving a country.

This concept is a reaction to western countries’ perceived loss of control of the state led control mechanisms over migration in the 80s and early 90s. Catalysts for migration which western states felt like they could not handle were the civil wars in Afghanistan or Angola, neoliberal reforms like the Structural Adjustment Programs (SAPs) that were instituted by western states, economic exploitation, political repression or the legitimate wish of finding better or simply different living conditions. Among those who were against a complete isolation from all kinds of immigration was the IOM. Instead they spoke of the opportunities of migration if states managed to maximize the advantages and minimize the disadvantages of migration. The implications behind the terms “positive” and “negative” follow neo-liberal logic to a tee. Migrants are split into two groups in respect to their economic exploitability; the “useful” and the “useless”. Those that serve the capitalist mode of production as cheap labor or highly educated specialists are considered useful. Those that find no place in the economy and are consequently criminalized are identified as useless. The latter are at the mercy of the hunting instinct of the cops and border patrol and are jailed or violently deported. Migration is not a danger for the IOM, if anything it can be a lucrative and should therefore be encouraged.

To reap the benefits from the wanted and ward off the unwanted people effectively the IOM stipulates that order must be brought to the subject of migration on an internationally coherent scale. The core of “migration management” is a categorization with which a state can neatly classify human beings:

1.Legal migration that should be supported:

Highly qualified labor, tourists, and students are economically beneficial immigrants and receive visas and further privileges relatively easily.

2. Illegal migration, which should be reduced:

A person not considered a “refugee” in a accord with the Geneva Convention, is criminalized. This person is economically undesirable, has no opportunity for legal work or domicile and has to live in constant fear of incarceration and deportation.

3. Forced migration, which should be protected:

The state should offer help to “refugees” that are officially recognized as such. This way the self-given humanitarian image can be retained by western liberal states.

The IOM is the biggest enforcer of “migration management” on the international playing field and all their programs correspond to this concept. The underlying logic of organizing migration along economical lines is the same in all programs.

The IOM trains border guards for a perfect border regime, conducts “voluntary return programs” – read deportation, helps states in the global mediation of highly qualified migrant labor, and operates scare campaigns with the aim of discouraging potential migrants.

The power and influence of the IOM over the migration policy

The IOM is funded by its member states. However, while all members’ funding goes towards the administrative branch, funding for the operational branch, which is responsible for the execution of the IOM’s migration programs, is optional. According to the list of member states that have funded the operational branch in 2016, the USA is by far the biggest depositor with 533 million US dollars followed by England, Canada, Germany, Australia, Sweden, and the EU, who is not a member. Switzerland contributed 6,699,200 US dollars to IOM programs. These are all states that have a marked interest in reducing migration and would profit the most from the organization’s programs. Welfare states such as these have accumulated their wealth through exploitation, oppression, and the destruction of habitats in other countries whilst having the arrogance to declare their standards and values as universal and forcing them onto others.

An “International Organization” (IO) is supposed to facilitate the cooperation between nations, at least that is often the justification for their existence. This line is parroted by the IOM: “IOM works […] to promote international cooperation on migration issues,[…]”. If this is what cooperation is, then so the wolf negotiating with the sheep over access to the water trough. In my opinion, an IO like the IOM is an instrument used by western states to assert their values and standards. The results of such alleged cooperation reflect the current power relations among nation states. For instance, Western Nations can exert pressure on the migrants’ countries of origin to adjust their migration policy according to the standards of “migration management” without being accused of violating their right to sovereignty. This happens, for example, at the IOM’s “African Capacity Building Centre” (ACBC). The ACBC acts as consultants to African states for questions concerning “migration management”. In effect, they offer training programs to standardize border controls, combatting human trafficking, and passport controls.

There are those who see the IOM as a completely autonomous agent with its own degree of power, independent from the interest of various nations. While I personally do not think that the IOM is purely an instrument, speaking of the IOM as an autonomous agent frees nation states from any responsibility and allows them to delegate migration programs that are in violation of international law or UN conventions to the IOM. This way they can preserve the image of a humanitarian country that upholds human and constitutional rights while simultaneously raising an admonitory finger at others without losing credibility. There are plenty of examples that western states do not give a shit about the “Universal Declaration of Human Rights” or international law, but like to hide the fact if the occasion arises.

There are enough men and women in academic circles who are devoted to the question whether IOs are just instruments or autonomous agents. I do not really feel like taking a stand on the issue and subscribing to a theory just to think that I can explain how the world works.

“Voluntary Return”

The more I read about the international level of migrations and its agents the more I see it as a cynical playing field for various agents (statesmen and -women, IOs, NGOs, economical stakeholders). All of this however, have real-world implications on the lives of people who are slowly being erased in this theoretical mess. Maybe they will appear more clearly in relation to the IOM if I introduce one of the IOM’s programs, the “voluntary return”:

Deportation is considered as a state-authorized handling of people who are not citizens but are national territory. It is popular practice in western states because this way they can ban migrants who do not meet the criteria for asylum from state territory. Despite its legitimacy, it is often not the most elegant practice for a humanitarian country such as Switzerland, for it is forced and violent and results in unpleasant stories and pictures.

The IOM offers a much better sounding alternative: “Voluntary return and reintegration”. The basic idea here is that with financial incentives and technical support, migrants will assist in their own deportation. According to the IOM, this way “migrants, who cannot or choose not to remain in the host country, have the opportunity for a humane return to and reintegration into their home country”.

They advertise it as a “win-win situation”: With the financial return assistance migrants have a positive outlook in their country of origin and the state has a cheap alternative to “forced repatriation”.

In Switzerland, migrants receive 500.- for a voluntary return at the “Empfangs- und Verfahrenszentrum» (EVZ). After three months of staying the amount is raised to 1000.-. Additionally, it is possible to receive a 3000.- assistance package for a so called “integration project” in the country of origin. To help set up a bakery or a kiosk, for example.

Instead of conducting these voluntary returns by themselves, the IOM offers their services to states and receives contracts like a business. Switzerland also employs the IOM’s service. For instance, the “Assisted Voluntary Return and Reintegration Program” for Nigeria that exists since 2005 is financed by the “Staatssekretariat für Migration” (SEM) and conducted by the IOM Bern. This program has a lot to offer: Return consultation in Switzerland, preparation of all necessary information and documents for a return, the organization of the return and the reintegration on the country of origin.

Even if the IOM speaks of a “win-win situation”, what Switzerland stands to profit is so big that it is hard to identify what the migrants win exactly. “Voluntary Return” is economically very lucrative for Switzerland. While a migrant costs 4000.- at worst for a “voluntary return”, a level 4 deportation costs between 8,000 and 10,000.-. On top of that, each day of detention pending deportation costs another 140.- and can culminate in 70,000 for the maximum 18 months.

There are countries that do not allow their citizens to be returned by “forceful repatriation”. “Voluntary Returns” are often the only possibility left for a deportation. People who come from such countries are left with no choice but to accept a “voluntary return”. The means to achieve this are manifold: up to 18 months in detention pending deportation, fines (high ones at that), prison sentences due to “illegal immigration”, banning from all kinds of work, around 8.- of emergency relief assistance per day, sleeping quarters in civil protection facilities often subterranean and the list goes on. It is funny how the voluntary and deliberate aspects are so highly praised with this program.

This system so full of freedom of choice even allows for the migrant to be made responsible for their own deportation. After all, Switzerland gives them the opportunity to leave out of their own free will and top it off with some cash. Urs von Arb, state secretary for migration, shows his regret that there are people who do not want to benefit from this offer and force him to make use of “forced repatriation”:

But unfortunately, there are people who do not want to leave voluntarily. So we say, listen, we’ll book you a flight. But they still refuse. They won’t be accompanied to an airplane by the police. So the police says, they must be deported on level four.

Does this mean that a level 4 deportation is voluntary return too? Or does the word voluntary in “voluntary return” refer to the decision to “voluntarily” forgo physical violence or to “voluntarily” give in to the pressure exerted by the authorities and the state apparatus of violence? Either all kinds of deportation are voluntary making the word meaningless, or all deportation is recognized for what it is: violent, forced and inhumane practices decreed by the state against people who have the wrong passport.

Yes, the IOM is a nasty organization

It is important to me that the IOM is included in the list of enemies in the fight against the migration regime. Their migration programs organize deportations, improve border security, produce “deterrent films” about Switzerland and much more absolutely shitty things. My main criticism of the IOM connects to that of nation states, of capitalism, sovereignty etc. One thing is clear to me, the IOM is very useful to western states for increasing their control over another aspect of international politics. They try to achieve this control over the migration policies of other countries not just through developing aid or other power games but also by giving qualifying their way of thinking as universal. With the development and propagation of the concept of “migration management”, the IOM dictates what kinds of migration exist and how they are supposed to be handled. “Migration management” is a concept developed by western states that all states should adhere to. It is offered as the only solution to effective handling of migration to the advantage of all parties. And as this definition of migration becomes more hegemonic in politics and our collective understanding, it becomes more natural to lock people in camps and to kick them to the streets because of some faulty paperwork.

For the author this text is a try to present one more actor of this hated migration regime. But it`s also some kind of revenge against the time spent in lecture and seminar rooms. Through academic papers and university lectures, the author got to know a little bit the game of the international politics. The rules of the game and the existence of the players hardly never got criticized but rather learnt as given.

– Andrijasevic, Rutvica / Walter, William (2010): The International Organization for Migration and the international government of borders. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space. Vol. 28. Pp. 977-999.

– Ashutosh, Ishan / Mountz, Alison (2011): Migration management for the benefit of whom? Interrogating the work of the International Organization for Migration. Citizenship Studies, Vol. 15, No. 1, Pp. 21-38.

– Geiger, Martin / Pécoud, Antoine (2014): International Organisations and the Politics of Migration. Journal of Ethnics and Migration Studies, Vol. 40, No. 6, pp. 865-887.

– Hanimann, Carlos (2010): Im Grenzgebiet des Rechts. WOZ, Nr. 28/2010.

– IOM Bern: http://www.ch.iom.int/

– IOM: https://www.iom.int/

Comment on three deaths of refugees in autumn 2017 and one still birth in 2014

Within the shortest time three refugees died due to police violence in autumn 2017 in switzerland. Subramaniam H. was shot dead by a policeman in Brissago/TI. In Lausanne, the police sought to transfer Lamin Fatty due to a mix-up and – to that end – held him in custody. The man, suffering from epilepsy, was denied medical aid and so he died in his cell. In Valzeina/GR, a young man from afghanistan was chased by the police to the point that he fell off a cliff and died. The silence of the media and the lack of consequences for the murderers demonstrate that, in switzerland, not all lives count equally.

The military tribunal seems to have shared this view when it punished a border guard – standing trial for the stillbirth of female refugee’s child – rather mildly. The border guard in question ignored the pregnant woman’s cries of pain, the blood running down her trousers and her husband’s pleas for medical aid, while they were kept in custody in the rooms of the border guard at the railway station of Brig in 2014. Despite the woman’s state, the frontier guard put the woman on the train to Domodossola and thus pushed off this “problem” to italy. Upon arrival, however, the premature baby had died. That woman was imprisoned, she was forced into the hands of a man who did not care at all about the fact that it was human beings he imprisoned. The woman had no possibility to get medical aid herself, and the baby is a dead human being, a killed child. It is this man, in the meantime standing on the platform and smoking, who is guilty of the child’s death. It is the migration regime treating human beings according to their economic value, that is guilty of this death. This is the true manifestation of the slogan „Borders kill“.

Everyday life in the deportation prison – A conversation in Bässlergut with two detainees

The following interview took place in the Bässlergut deportation prison during the official visiting hours. Standing in front of the large prison gates, we press a red button and via intercom give the names of the people we want to visit. The first door opens; before being allowed through the second we have to wait again; ultimately, we are let in and after a few metres we enter the overheated entrance area of Bässlergut. Take off the winter jacket, hand in the ID-card, deposit our bags, fill in the registration form, go through the turnstile and pass the metal detector. As always, we are taken one-by-one to the visitors’ room where we take our seats and wait until finally, we are five of us at the table. Although we all already know each other, the two detainees we’ll be interviewing are rather mistrustful at first. They show this by not only wanting to know why we wish to interview them but also who we work for and whether we are affiliated to any (political) group or association. The interview is very risky for the two detainees, as they are subject to the capriciousness of the wardens. Recognising this, we would like once again to thank both for allowing us to publish our conversation.

You‘re about to have a level 1 deportation.1 Will you resist this?

B: Yes, I‘m being subjected to a Level 1 deportation. I can’t cope with going through all the levels again and then getting kicked out a third time so violently. No, I really don’t want that. I don’t know, when exactly I will be deported. I will only hear about 2 to 3 days beforehand. It doesn’t bring much to resist anyway; it would only defer the deportation by 2 to 3 weeks.

N: The problem is that we are just seen as foreigners. That we’re also humans gets forgotten.

B: I grew up here and now I‘m being deported and can’t stay with my child. What I really want is to live here, look after my family and see my child grow up! Actually, I never wanted to put kids onto this fucking world. But now I have one and have to leave. I won’t be able to see how he develops, how he eats, speaks or walks for the first time.

What’s your everyday life look like here in Bässlergut?

B: At 7:15 the guards open the door to our cell and at 17:00 it’s closed again. There are three of us living in our cell. We have a TV there. In addition, there’s a common room on our floor with a kitchen and a large table, but only two chairs. It’s not cosy there at all.

N: Being able to go out helps the time pass. Some go out, a few stay inside. Twice a day we can go into the courtyard, once for an hour and once for two hours.

What about the food?

B: Breakfast is at 7:15 and we have something to eat again at 11:00 and at 17:00. Second-helpings are out. Once we asked the guards if we could order a pizza and pay for it ourselves. „Fuck you,“ was the answer.

N: A small kiosk is open once a week where we can buy food, drinks, cigarettes and other things. But they are completely overpriced: An M-budget chocolate bar costs about Fr. 2.00.

N: A small kiosk is open once a week where we can buy food, drinks, cigarettes and other things. But they are completely overpriced: An M-budget chocolate bar costs about Fr. 2.00.

B: I work 2½ hours a day and can hardly buy anything with what I earn!

And what about the work?

N: In the evening, the prison wardens come and ask who wants to work the next day. On Monday, Wednesday and Thursday the working hours are from 8:00 to 10:30 and on Tuesday and Friday from 14:00 to 16:30.

B: Two to three people sit at each work-table. We are not allowed to talk. You can only drink water from a tap in the toilet. We’re not allowed to drink water while working.

What sort of work do you do?

B: At the moment, we’re mainly doing things for Christmas, for example, assembling different packages and gluing pieces together. When they’re finished, the packages are then sent to Belgium, where they are filled with various things. From there they go on to China. But I don’t know who the order is for.

N: For the two and a half hours we work we get Fr. 7.50 each.

B: Last week my wife and child came to visit me when I was working. At the reception they asked to see me, but nobody came to tell me that my family was here. So, they left again. When later I found this out later, I asked the guard why he hadn’t informed me. Seeing my wife and child is more important to me than shitty Fr.7.50! „Those are the rules: When you agree to work you have to work.“ was the answer I got.

N: Withdrawing the allowance to work is sometimes used as a form of punishment as this means you aren’t able to earn any money.

Do you work?

B: Yes, I work regularly. But not because of the money. No, the only reason I work is that I sometimes need to get some peace. Otherwise all around me people are always listening to music, talking on the phone or talking to other people. By going to work, I can escape the hubbub for a short period of time.

N: No, I don’t work anymore. Three months ago, I broke a small carton box while working. It was only about as big as an A4-sized page …

B: That can happen; it‘s all happened to all of us some time!

N: … I got bunker-arrest for five days. I haven’t worked since then. I don’t want to risk having to go there again.

Can you tell us something about the bunker? What’s it like?

N: It’s an isolation cell used for solitary confinement. In my case, for breaking a small cardboard box at work. During the time in the bunker I was only allowed to walk in the courtyard once a day and on my own; the rest of the time I spent isolated in a room with a small window and a TV. After five days, I was finally able to return to my cell.

What kind of medical care do you have?

What kind of medical care do you have?

B: There are two doctors you can go to. One is not helpful at all. He treats us aggressively. We speak different languages which often leads to misunderstandings. We are as unimportant to them as we are to the guards. You can tell by how they talk to you and how they deal with you in general. One detainee in our cell swallowed a lot of shampoo once. He had mental problems and hadn’t eaten for a long time, but he smoked like a chimney. Do you think the guards arrived straight away when we called for help? No way, they only got here after three-quarters of an hour, although they could have made it in five minutes. That shows how we aren’t taken seriously here.

N: Two weeks ago, I asked the psychiatrist who treated me two years ago, to come over because I wasn’t well. However, the prison guards told me that this wouldn’t be possible and that I wasn’t even allowed to ask.

Walking past the turnstile to the visitors‘ room, one can see on the right-hand side a cupboard full of various medicines. Do you get the medication you need? And what medicines do you get?

B: Yes, we can get medication. All the medicines we take have already been dissolved in water. It isn’t possible to get medication in the original packaging. I bet there‘s Temesta in it as well. When I asked if I could get my medicine in its original packaging, I was told, „Shut up, you shit foreigner.“ Since then, I have stopped taking medicines because I see what happens to everyone else: either they calm down and sleep or they become aggressive. By the way, the same thing happens after dinner: We all go to sleep afterwards. That‘s not normal! Or do you go to sleep every time you eat? There is certainly some sort of tranquilizer in the food.

How do you get on with each other?

B: We spend most of the time on our own – each of us in our own part of the cell. Everyone tries to cope with their problems by themselves. Especially if someone has been badly treated, then he can become very aggressive. Then it is better to leave him alone for the time being. Added to that, we have difficulties communicating with each other, as we speak so many different languages.

Are there any collective forms of resistance?

B: Once somebody went on a hunger strike for seven days. Then the guards put him in the bunker and gave him some medication. Even in our cell, we’ve thought a few times about going on a joint hunger- or work-strike and we already started planning one once. But there are always a few detainees who don’t want to join in. I can understand that too: If you smoke, you just need to go to work. That‘s why such plans to resist fail.

N: Actually, one could say that the only way to survive here is to try to stay stable. Because they want that: to break us mentally.

Do you feel any solidarity from outside the walls of Bässlergut?

B: No; and, if so, then only through visits from outside. Anyone who doesn’t have any visitors doesn’t feel any solidarity. Once you‘re in jail, you‘re stigmatised, you don’t have any friends any longer. When you‘re in jail, suddenly all your friends are gone and nobody comes to visit you. That‘s the way it is…

Gegen wen richtet sich eure Wut?

N: When I was outside, I didn’t know what the deportation prison is like. Now I‘ve been here for four months. What’s done here to people, doesn’t happen anywhere else. If I ever get out, I’ll come back to Switzerland and demolish this prison. Since being here this has become my goal.

B: As a foreigner, you can do little to change your situation. Even if you‘re born here and have a Swiss passport, you‘ll always be a foreigner. This Blocher, who earns millions every year and stirs up resentment against foreigners. Who works for him? Who cleans his toilet? And he says “shit foreigners”! In this world, the mightier one always wins. That’s reality. Switzerland is said to be neutral. But who supplies weapons to the rest of the world? Switzerland is said to be neutral. But that‘s just not true. Switzerland is a police state. Once the prosecution has decided what’s going to happen to you, it’s closing time. Is your lawyer a member of the SVP? Then it’s closing time. They can offend us foreigners as much and as often as they want. We’re here and just have to shut up.

Prison Sucks – 6 surprising reasons why we should fight prisons

Prisons are socially implicit, they seem unassailable. Throughout the political spectrum, from the left to the right, there is rarely any criticism aimed at this institution. This used to be different, prisons are a modern phenomenon. Here are some ideas which could break through this implicitness.

Even the radical left has been withdrawing their demands in the past decades. While during the 70s- and 80s the „Entknastung“1 (minimising prisons) of society was their focus point, all people dare mentioning today is the disimprisonment of „our“ political prisoners.

Prisons

Prisons have existed since antiquity, but for a long time their function differed from the function of prisons today. People were put in prisons temporarily until the proclamation of the sentence or the execution, similar to today’s imprisonment on remand.2 The punishments were monetary fines, public humiliation like the pillory or banishment, as well as corporal punishment like floggings or death penalty.

Debtor’s prisons were also very common: people were imprisoned until they settled their debts or were able to do so. This has changed: People in debt must serve their fines in prison.

Work and correction houses arose only later, in England. They were for marginalised groups and the poor so they could „improve“. From that point forward, more focus was put on punishment by incarceration as it is considered more humane than public humiliation and corporal punishment. In the 19th as well as the 20th century, there were efforts and movements to reform this system which demanded that prisons become a place for people to better themselves or be converted.

The punishment consequently disappears behind high walls from the public eye through the imprisonment. A complex, systematic correctional system with different levels of incarcerations, from adjustment of penalties, work, leave, to yard exercises and so on.

The idea remains: the body needs to reside within the building and abide by the executive power – frequently appointed by the state.

Reason 1: It creates more problems than it solves

Next to the fact that a prison itself is a form of violence, many detainees become victims of violence by inmates or guards. There might be people incarcerated who are suffering from some form of trauma; it is also very likely that they will live through traumatic experiences in prison. The repressive surroundings, the hierarchical structures and living conditions enhance depression, pathological addictions, power games, and violence to and by the prisoners. For example, the highest drug prices can be found in jail.

It is absurd really that in big prisons „lawfree“ space is created, in which violence, rape, drug-trafficking etc. are on the agenda. Environments are created which make it possible to develop problematic strategies to resolve conflicts such as violence, let alone acting them out and passing them on. A prison is a place where delinquent practices and strategies are dispatched and spread. An underworld exists which hardly anyone knows let alone is interested in. It is, after all, happening behind high walls.

Many young people, who are arrested because of „small“ delinquencies, will get in contact with a environment in which delinquency is reputable and widespread. In certain cases, prison will foster the criminality it promises to fight and will do a lot of harm in doing so.

Reason 2: Society produces „superfluous people“

Prisons are full of people who came into conflict with the law through social inequality and poverty. Most of the sentences are directly or indirectly connected to questions of property. Many prisoners are users of illegal drugs. The prison, the instrument of sovereignty, is not only oppressive but just as productive: people are urged to behave productively and to conform. It is these instruments which constitute us and our society.

Many laws are part of the war against the poor. They are created to stipulate and defend the present order and existing structures (of ownership). The justice system is not as neutral and objective as it seems. What should be pursued and penalised is a political decision which so far has brought absurd dimensions (such as prison for fare evasion). Laws create a class of and legitimise delinquents and a whole apparatus of policemen and women, judges, supervision and control. Prisons, just like schools, barracks, psychiatric institutions, hospitals etc. show the individual their place in society and determine them in that exact position.

Theoretically, one of the goals of incarceration is resocialisation. The individual should take a different, more conforming position in society again. These were the goals of many reforms in the last decades. They seem to have been abandoned by now.

As long as society is as it is – full of social differences, sexism and racism – there will always be people who get into conflict with the law. Society will always produce „superfluous people“.

Reason 3: It should scare us

The simple awareness of prisons and prisoners should serve as deterrents. The fact that you could lose your liberty when breaking the law will make you aspire to conform and be as law abiding as possible. This fear needs to be present in our everyday life as well as our subconscious: The police in your own head. This already helps to prevent the smallest transgressions. Something that is seen as characteristic for pacified countries like Switzerland.

Reason 4: We love freedom

The most blatant deprivation of liberty: prisons are an especially strong form of an in- and exclusion mechanism. Resistance to and criticism of the existing order can quickly lead to imprisonment.

Reason 5: Why punish?

Is punishment a moral idea, an appropriate reaction to offences like theft, violence, or assault? Punishment always means to purposefully make someone suffer. What is the goal of making someone suffer? – The thought of punishment is based on an idea of retaliation and revenge. Delinquents are stigmatised and through this the resocialisation – which should be one of the reasons for prisons – is impeded.

The demands for severer punishments are getting louder. This is a deeply reactionary idea based on the moral concept of retaliation towards those who supposedly refuse to stick to the ruling order.

Reason 6: Sexism and racism

The people in prison are mostly men. The prisons contribute to (re)producing sexuality and gender. While men are more likely to be accused as perpetrators, women are presumed to be insane and are put into psychiatric care. Unfortunately, sexualised and racist violence are on the agenda in both institutions. The state is not able to keep its promise of security, quite the contrary: techniques and institutions like the police, prisons, borders etc. produce violence against women* and people of colour instead of stopping it.

The protection of marginalised communities is used as a pretense to have the police and the judicial system continue to resort to violence. Let us look at the example of the discussions after the incidents during the night of New Year’s Eve 15/16 in Cologne: The violence against women is a widespread and often hidden phenomenon, and is used to legitimise violence against People of Colour, in the country as well as in so-called „EU external frontiers“. If an illegalised person becomes a victim of sexual violence they might not have the possibility to turn to the police. They could experience violence once more: they could be incarcerated and deported.

Community based approaches

So how to feel safe if there were no prisons and the police are of no help?

There are some approaches from queer-feminist circles which have already been applied many times with mixed results. The idea is that the environment of the perpetrator and the environment of the „victim“ can try to find a way to handle the experiences of the „act“ and to understand and work out the consequences. Many of us have certainly done that with small offences, assaults and problems in the social environment. The following principles have been worked out by people who have worked on this topic extensively.3

- Collective support, security and self-determination for the affected people.

- Responsibility and change of habits of the person who used violence.

- Development of the community towards values and practices directed against violence and oppression.

- Structural and political change of the conditions which have made violence possible.

Consequently, the people using violence are offered the possibility to change their behaviour instead of being punished and cast off. It is more about empowering the people affected by the violence instead of just protecting them. The “victim’s” self-determination needs to be reclaimed and they should not just receive protection from the outside as a „powerless“ person. This strategy is at the core of the assumption that the people who have been affected by violence have great knowledge and skills that will make them into potential participants of their own as well as societal change.

This is an entirely different approach than prisons are, which want to sell us security through the safekeeping of danger. This prison-logic tries to isolate a few „rotten apples“. But often there will be good explanations 4, albeit no excuse for violence.

All these approaches are only possible if the people have social environments that are stable enough, and see themselves able to act and intervene in a violent situation. To make this possible for all people we most likely need to live in a different world. The reasons for a fight against prisons do not only have to do with criminal justice and the state but are also questions about an emancipated and just world.

A person who in the last few years has started to engage in the topic of deportation and the deportation prison „Bässlergut“, has developed a fundamental critique of the institution. This person cannot understand, why resistance against the expansion of prisons has never led to a discussion of sense, nonsense, and necessity of the institution of incarceration. This text is based on an input given in the fall of 2017 at the „Bässlergut-Wochenende“ at bblackboxx.

«I don’t expect anything much from life anymore»

Fahim sits in front of us and nods his head in a friendly way. We take this to mean we can start the interview. The young man doesn’t seem to care too much about what we do in our lives, how we make our money or if we belong to an organisation. Fahim tells us he has been in the deportation prison Bässlergut for some months now pending deportation. Before this he had spent several years in various other prisons – firstly in a juvenile detention centre and then in adult prisons. He says he has been in prison for far too long and is sure he must have more than finished his sentence by now.

When asked how the everyday life in an ordinary prison differs from that in a deportation centre like Bässlergut, he names the opportunity to work. In prison Fahim was responsible together with eight other inmates for preparing lunch and dinner for 140 people.

It was a strenuous job, and in the evening, I knew how hard I had worked.

For the 6½ hours a day that he worked, Fahim received 22 Swiss francs. He managed to save some money so that he doesn’t now have to work in Bässlergut.

Conditions in the deportation prison

Fahim tells us that the inmates in Bässlergut get on well with each other in general, even if communication is difficult, as most speak either English, French or Arabic but not German. He spends most of his time sleeping and doesn’t have much to do with the other prisoners or the wardens. He only sees the latter when he gets medication (for his gastric acid reflux), a shaver or food. Otherwise he’s by himself a lot. Until recently Fahim shared the cell with another inmate, but now he has been deported, Fahim has the cell to himself.

That doesn’t matter to me. On the contrary. I prefer to be alone. I don’t care what the mood in the prison is or how the others are doing. I’ve had enough of it all.

Ten people are currently detained in Fahim’s wing of the centre and all should be deported as soon as possible. The wing has single, two-, four- and eight-person cells, as well as a common-room with table football, a kettle for making tea, a table and three chairs.

Just yesterday an observation camera was installed in the common-room. Probably because some inmates smoked cigarettes while playing table football.

Unlike prison, the food here is awful, Fahim tells us. “Sometimes there is only soup and a piece of bread in the evening”. Everyone eats on their own in their cell.

Impending deportation

The first time Fahim heard that he was going to be deported was in a letter. This listed his crimes and the grounds for the deportation. Although Fahim put the letter aside, he tells us, he never forgot it. In fact, he always believed that he would be freed after having served his sentence. He received the letter at a time when he was on the run, having absconded from an open prison. But after a few months he turned himself in to the police. Because he had absconded he wasn’t allowed to return to an open prison but had to go to a detention centre instead, where he spent a further year.

The first time Fahim heard that he was going to be deported was in a letter. This listed his crimes and the grounds for the deportation. Although Fahim put the letter aside, he tells us, he never forgot it. In fact, he always believed that he would be freed after having served his sentence. He received the letter at a time when he was on the run, having absconded from an open prison. But after a few months he turned himself in to the police. Because he had absconded he wasn’t allowed to return to an open prison but had to go to a detention centre instead, where he spent a further year.

At the detention centre you‘re in your cell for 23 hours a day and are only allowed out for one hour. It wasn’t until I wrote to the authorities that I was allowed to leave the detention centre.

Why he had to stay in the detention centre for such a long time, he still can’t explain. After the detention centre and following his trial Fahim spent a further two years and nine months in prison.

The authorities there are the worst when it comes to applying for early release on grounds of good behaviour or for holiday permits. I was neither granted leave, nor was I released early for good conduct. But that didn’t just happen to me, it was the same for most of the others too.

Two weeks before his release, he was told that he would be moved to Bässlergut in order to prepare for his deportation. Ever since then, Fahim has been fighting to be released, but a request to the Court of Appeal for discharge was denied. Although Fahim – as he tells us – hasn’t entirely given up hope, it’s diminishing day-by-day. Asked what he would do if he were actually released, Fahim says he would go to Sri Lanka for up to three months.

After that I would return to Europe, either to Germany or Austria, where I would have to stay at least five years before I could enter Switzerland again.

He tells us that he already has contacts in Austria. He knows a boxing club there and has already sent them videos of him boxing. The club would like to take him and would help him look for a job.

Prison & deportation as seen by Fahim

For Fahim a B-permit means much the same as an F- or C-permit. His younger brother and his father both have a C-permit; his mother a B-permit. Why his mother hasn’t got a C-permit despite being employed and having lived long in Switzerland, he doesn’t know. Like him, his older brother is in custody and is also threatened with deportation. Five years ago, a friend of his was deported to the Ivory Coast. „He’s in bad shape there, because all his relatives are in Switzerland“. Fahim thinks that a prison sentence may sometimes make sense, especially if it can help you gain an insight into your behaviour. When we ask Fahim if he would have given himself a prison sentence, he replies,

I have committed many crimes; even the police don’t know about many of them. Altogether, I think 4½ years in prison are warranted. Somehow or other I’ve earned such a long prison term.

However, he finds it difficult to accept that, after having served his prison sentence, someone should then be deported. He cannot understand how one can take everything – even family and friends – away from a person. Furthermore, he finds it absurd to invest a lot of money in integrating somebody into society, only to subsequently deport him. Fahim points out that he has changed a lot over the years and learned a great deal, but this doesn’t seem to interest the authorities. Although he has been living in Switzerland for 17 years and has no ties to Sri Lanka, he should be deported there.

I’ve paid my debt to society, served my sentence in prison. Now I am waiting for a miracle.

Politics and perspectives

Before he went to prison Fahim hadn’t thought much about prisons or deportation. „As long as you don’t have anything to do with them, the whole thing seems far away“. Fahim doesn’t know whether in the future he wants to fight against repressive measures such as imprisonment or deportation. He assumes that people would then point a finger at him and call him a criminal. To go to a demo would take a lot of courage for him, as they often end up with a confrontation with the police. His friends aren’t politically active either.

When I‘m released, I don’t want to do anything but work, box and spend time with my family. I don’t expect anything great from life anymore.

This article is based on a conversation the authors held with Fahim. For Fahim it was important that the article covered everything that we talked about and not just focus on one main point. Before the interview Fahim was offered the opportunity to narrate freely, but he preferred to answer questions which the authors had prepared in advance. The authors of this article have been arguing against Bässlergut for a long time. Their fundamental criticism of the prison is based on their rejection of the rule of one over others.

WEek END BÄSSLERGUT

Since the beginning of the year the deportation prison Bässlergut, at the Otterbach border in Basel, is being enlarged with a second building. With a discusion weekend from the 6th to the 8th of October 2017, taking place around the Bblackboxx, right next to the construction site of the new building, we wanted to share our criticism about this project with as many people as possible.

We wanted to exchange thoughts on these relations, our utopias and ways to resist. At the same time being present at this site should become part of the resistance against prisons, borders and repression. The event was organized by individuals who had been involved in these topics already an found together through it.

Diverse critics on the conditions that manifest in Bässlergut

The program started on Friday evening with a well attended NO-Lager-tour around the reception- and processing-center (Empfangs- und Verfahrenszentrum EVZ) the already present deportation-prison Bässlergut I and the construstion site of Bässlergut II. The knowledge of the day-to-day conditions behind these walls that had been collected in conversation with detainees was shared. This was followed by an input on the developments and relationships between the asylum- and justice system. This input made clear that the new building Bässlergut II is an expression of a development which will lead to a future where more migrants and destitute people will be imprisoned – who often are the same, going back and forth from deportation prison to penal prison in the new building.

The program started on Friday evening with a well attended NO-Lager-tour around the reception- and processing-center (Empfangs- und Verfahrenszentrum EVZ) the already present deportation-prison Bässlergut I and the construstion site of Bässlergut II. The knowledge of the day-to-day conditions behind these walls that had been collected in conversation with detainees was shared. This was followed by an input on the developments and relationships between the asylum- and justice system. This input made clear that the new building Bässlergut II is an expression of a development which will lead to a future where more migrants and destitute people will be imprisoned – who often are the same, going back and forth from deportation prison to penal prison in the new building.

With a general criticism of the prison as an institution throughout the last 200 years the Saturday session was opened. In small groups the subjective sense of security was discussed. It became apparent that a strong sense of social security in ones circle of friends or in political contexts was important. Whereas the structural security e.g. having a Swiss passport and the privileges that come with it played a less important role. Can one fear starvation when one has never starved? One of the participants described their privileges also as dependencies that can be withdrawn when one doesn‘t stick to the rules of the game (freedom of movement, various social services).

Through the initiative of a group of people who regularly visit prisoners in Bässlergut and prisoners themselves, a visit to the inmates took place to show solidarity. For a lot of the participants this was a new and important experience. And also the inmates were happy about this support. A regular visitor of Bässlergut prisoners said that he had never seen as many people in the visiting room of the prison before. This collective visit has led to organized, monthly visits (Agenda, S.70). Parallel to the prison visit, an introduction in the historical development of the idea and practice of custody was given. Under this term in Switzerland there exists a years long or lifelong imprisonment that can be ordered by psychiatrists with the help of computer programs. The discussion that followed in small groups was dedicated to the question of how a helpful practice (in solidarity) with mentally ill people should look like. A central point of the discussion was the criticism that psychiatric clinics dehumanize and try to “normalize” patients as well as the lack of knowledge and discomfort when dealing with mentally ill people in ones environment. To be able to help those affected by mental illness, one needs specialized knowledge and a social environment sensitive to their needs.

Later in the afternoon a brief story was told of how prisons in the U.S.A are currently being privatized. Prisons have become a lucrative business for private companies. Various international companies (including European ones) compete on this market, doing lobby work to establish more restrictive laws, exploiting prisoners as a cheap workforce.

Later in the afternoon a brief story was told of how prisons in the U.S.A are currently being privatized. Prisons have become a lucrative business for private companies. Various international companies (including European ones) compete on this market, doing lobby work to establish more restrictive laws, exploiting prisoners as a cheap workforce.

The day ended with a film-screening by Kino Vagabund: Fragments of “Vol spécial” by Fernand Melgar and the short movie “Einspruch VI” by Rolando Colla. After the two movies, a controversial discussion began: Are consternation and identification with the victims of the deportation regime the right conditions for a political fight? Are the films demonstrating structural relations and taking a clear position to these? And, what use is it to watch, when one should spring into action?

On Sunday morning, a migrant without papers explained his way through the Swiss camps, prisons and psychiatries and how he ended up in a political environment, fighting for his own rights. He then described how an active resistance against the present system and the practice and exchange with like-minded people allowed him to have a long-term perspective in Switzerland.

Early in the afternoon, questions of privileges, guilt and solidarity were being defined and discussed in a workshop. One person without papers, that had been arrested for several months, said, that to him, visits in prison were a strong gesture of solidarity. At the same time he criticized that in Switzerland the equalization of the terms solidarity with the terms charity and charitable work is often being made. In some groups, there were also discussions about whether or not privileged people should use their privileges in a fight based on solidarity. This could be dangerous: It could reproduce the structures that generate these privileges. Another option would be to fully refuse structures that produce privileges, but this goes with a loss of possibilities to support others.

Food for thoughts about resistance

Our critical presence close to the new prison Bässlergut II, the deportation prison Bässlergut I and the EVZ was creating a form of resistance. There were many lively discussions, in which different topics were treated and critically examined. The presentations filled with interesting content and the broad spectrum of critique showed many structures and practices that need to be fought. It remained difficult to find ways how to translate this knowledge and exchange into a practice of resistance. In this way the weekend was raising indeed the wish to act, but didn’t really open up new perspectives of action. Instead it left some participants with a feeling of powerlessness. The question how and where shared knowledge can be transformed into a practice could have more importance in the planning of a further event like this one.

Several directly affected people insisted on the fact, that authentic and effective resistance requires a bigger willingness for actions that question also the life of one’s own and bring about risks (like money or prison sentences or the loss of privileges). Maybe it is indeed true, that people who are not yet living in a perilous situation, should take resistance more seriously and don’t let themselves stop by the risks that come along with it.

What use is it to watch, when one should spring into action?

During the mobilization process for the event we were often confronted with superficial questions about the deportation policy, but during the weekend the discussions were almost exclusively lead in a principal anti-capitalist mindset. The predominant discourse in this society on deportation policy in the style of “it is indeed a human tragedy, but nonetheless not all of them can come here” was not an issue during the weekend. This is on the one hand a comfortable basis for deeper discussions, on the other hand it can make us forget, how much every kind of alternative to the current migration regime requires a fundamental change of this society and can only be understood on this basis. If migration policy should change, the whole political and economical system must change, which also implicates a fundamental change of society.

Commonalities and exclusions

With around two hundred participants despite the cold and rainy weather, the event was quite well attended. People from the EVZ were present, although they were not participating much at the different activities, even tough they have been informed beforehand about the topics and possibilities of translations. The question arises if the framework of presentations with discussions is suitable for an exchange like this. Anyway, thanks to the excellent and permanent food supply the breaks were used to eat together and have more discussions in small groups.

With around two hundred participants despite the cold and rainy weather, the event was quite well attended. People from the EVZ were present, although they were not participating much at the different activities, even tough they have been informed beforehand about the topics and possibilities of translations. The question arises if the framework of presentations with discussions is suitable for an exchange like this. Anyway, thanks to the excellent and permanent food supply the breaks were used to eat together and have more discussions in small groups.

Despite the spicy topic, the police appeared only two times openly on the spot. But still the repression had its effects on the weekend. Some interested people were on the other side of the prison walls and some others didn’t dare to attend the event because of the danger of prosecution and arrest.

Outlook

On the 30th of October there was a further meeting at which the discussions focused more on perspectives and possibilities of resistance. At this meeting the necessity of a long term, open and transparent organization as well as the direct intervention in the public discourse and conditions became evident. Regular public exchange meeting are planned. And also other kinds of actions and discussions (like the collective visits in the prison Bässlergut I since the weekend) continue in a public way.

The construction of Bässlergut II continues until 2019 and probably the conditions materialised by it will persist beyond this date. An infrastructure that is being built, will be used in consequence. The joined resistance in discussions and actions against it remains a necissity!

The try to close the central mediterranean route

In November 2017, ministers from 13 states and representatives of several intergovernmental organisations met in Bern for the third meeting of the Central Mediterranean Contact Group. Sommaruga told the media how this panel apparently had saved 14’000 refugees from drowning and how it had stood up for better conditions of imprisoned migrants in libya. This sounds great but what is behind all of this?

The truth is that the libyan coastguard – financially supported by the participating countries – got 14’000 people off their boats shortly after they had set sail, and then imprisoned them in libyan detention camps. The fact is that the Contact Group is mainly pursuing a strategy that wants to see the issue of migration as far away from europe as possible. The three most important priorities formulated by the Contact Group correspond to their strategy:

1. To strengthen the libyan coast guard.

2. To increase the capacities for the protection of migrants in libya.

3. To control libya’s Southern border.

It is that exact policy that led to the closing of the Balkan route by means of a dubious deal with turkey one year ago. This policy was continued this summer when the central Mediterranean route was partly closed – much less noticed by the public than back in 2016. The partial closure went through mainly thanks to the efforts of italy’s prime minister Mitini who signed numerous official and unofficial deals with various warlords, militias, the libyan coast guard and libyan mayors. It seems that the various libyan players were successfully persuaded by these deals to prevent the refugee boats from sailing off the libyan coast.

The maritime sovereignty zone of libya was extended to 100 kilometres off the coast of the country. It had previously been 12 kilometres. This means that within this strip only boats of the libyan coast guard are allowed to patrol and save other boats from distress. The libyan coast guard fired sharp ammunition at a lifeboat upon its entry into the 100 kilometre zone. And yet, according to Sigmar Gabriel, there are no alternatives for the eu other than financially supporting that same coast guard as well as the libyan unity government who runs the above-mentioned detention camps.

At the same time, the eu forced various charities, active on the Mediterranean, to sign a code. This code includes the duty to take an armed policeman*policewoman on board rescue lifeboats. Furthermore, the code forbids any hand over of rescued people to bigger ships. The latter would have the consequence that smaller ships would have to sail to italy after every rescue and would thus not be able to carry out further rescue operations for several days. Fortunately, there were a couple of organisations who opposed this policy and did not sign the code. Medecins Sans Frontieres, for instance, states, that:

This Code seems to be entrenching the view that states can outsource the life-saving response to NGOs, allowing states to concentrate their efforts on naval and military operations.8

Organisations that did not sign the code were threatened with being banned from using italian ports. In addition, there were several cases of undercover investigators and bugging devices being brought on board of rescue ships. One ship, owned by the organisation Jugend rettet, was even confiscated by the italian police. A media campaign then propagated the cynical assertion that by rescuing people from the Mediterranean NGOs actually work as pull factors and therefore bear the main responsibility for the many casualties. Without any doubt, an attempt to defame the charities’ valuable work.

The strategy chosen by the Central Mediterranean Contact Group made a visible impact. Since July, the numbers of attempted passages from libya to italy are permanently low, while the detention camps are filling up. In libya, people are forced into slavery and prison camps, and exposed to rape and abuse. A quote by Sommaruga illustrates the double benefits of this strategy for european countries. On the one hand, the violent treatment of migrants is successfully moved even further away from pacified europe, on the other hand, the european states can show off their cloak of humanity:

We have to be able to get the weakest quickly out of libyan detention camps. The situation there is absolutely terrible. This also affects all the other migrants such as the numerous migrant workers stranded in libya and who are stuck there now. It is them we have to support so that they return to their countries of origin voluntarily, because it is unlikely they will receive asylum in europe, they only risk their lives when crossing the Mediterranean.

The fact that migrants continue to arrive, despite the strengthened repelling mechanisms, clearly shows that europe’s wealth rests on the three pillars of violence, exploitation and war. This, however, does not fit in the picture of europe’s self-perception. In my opinion, the goal of the strategy is to shield europe from the consequences of war and misery for which it itself is responsible. The fact that in pursuing this strategy, europe is not afraid to resort to military means seems nothing but a logical consequence.

europe is at war with refugees and it is a war waged on several different levels. Yes, you read correctly, war. Because it is war. A war at the borders, against migrants; a war that serves europe as means for exploitation and retention of power but also for the pacification of europe and the preservation of privileges. This is shown by the surveillance of the borders by military forces in libya as well as in europe . This is shown by the detentions camps in which people are imprisoned, both in libya and in europe . And it is shown by the people killed by the border regime, both in libya and in europe.